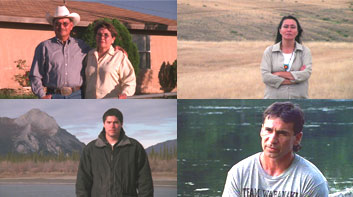

Featured Activists

Featured Activists

Gail Small, Northern Cheyenne, Montana

Gail Small is an attorney and long-time activist leading the fight to protect the Northern Cheyenne homeland from the ruin caused by 75,000 proposed coal bed methane gas wells – wells that threaten to salinate the Tongue River and make much of the reservation unsuitable for farming or ranching.

“You put in 75,000 methane gas wells around our reservation, you take our ground water, pollute our air, destroy our rivers, and the Cheyenne will probably not be able to survive,” says Small. “We’ll have a wasteland here.”

Small was born and raised on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. A graduate of the University of Montana with a law degree from the University of Oregon, she has been fighting the energy companies’ efforts to encroach upon Cheyenne land for much of her life. As a teenager, she was immersed in the infamous Montana Coal Wars – a grassroots struggle to reverse government policy allowing companies to mine the rich coal reserves under the reservation.

“At 21, I was the youngest member of the tribal negotiating committee working to get the coal leases cancelled,” Small says. “It took 15 years, but we finally won.”

In 1984, Small founded Native Action, a national model for citizen empowerment on Indian reservations. Native Action has established national precedents in federal banking law, environmental policy, Indian voter discrimination and youth law.

Small has served as an elected member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribal Council and remains active in national Indian policy issues, as well as international indigenous issues. Her work has earned her numerous awards, including Ms. Magazine's 1995 Gloria Steinem Women of Vision Award.

Small lives with her family in Lame Deer, Montana.

Evon Peter, Gwich’in, Alaska

Evon Peter is the former chief of an isolated community that is at the forefront of the movement opposing efforts to drill for oil in the fragile Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. At risk are the Refuge, the caribou that give birth to their young there and the cultural survival of the Gwich’in people.

“All the villages and tribes of the Gwich’in Nation are lined up along the route of the porcupine caribou herd,” says Peter. “Their survival is our survival.”

The Gwich’in Steering Committee was organized in 1988 by elders and leaders of the Gwich’in Nation to protect the birthing grounds of the porcupine caribou herd upon which the Gwich’in depend.

“This is all we have. We don’t have Safeways and Wal-Marts,” says Peter. “But it’s also about maintaining our culture and the spiritual relationship that we’ve had with these animals for time immemorial.”

Raised traditionally in Arctic Village, Peter left home to pursue a degree in Alaska Native studies and political science. Upon returning, he became the youngest chief in Gwich’in tribal history at age 23. Though he made his home in a small village of scattered wood cabins (with no running water or electricity), Peter was a well-traveled advocate for his tribe – Internet-savvy and comfortable negotiating with government officials and speaking before audiences at world conferences on the rights of indigenous peoples.

Peter is co-chair of the Gwich’in Council International, chairman of Native Movement and on the executive board of the Alaska Inter-Tribal Council. He is married to Navajo activist Enei Begaye and is pursuing a masters degree in urban development at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks.

Mitchell & Rita Capitan, Eastern Navajo, New Mexico

A married couple with four kids, Mitchell and Rita Capitan were the unlikeliest of activists. But when they learned that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) had approved a permit to mine uranium just miles from their home in Crownpoint, New Mexico, they decided they had to do something.

Mitchell and Rita Capitan founded ENDAUM (Eastern Navajo Dine Against Uranium Mining) to rally their community to stand up to the nuclear power industry, the NRC and even the US government.

“We’d never been involved in politics or anything like that before,” says Rita. “But with grassroots organizing and endless legal challenges, we’ve been able to block new mining for nearly a decade.”

The Navajo have a long and painful history of uranium mining dating back to the post-World War II push to use domestic uranium resources. Many companies hired Navajo men to work the mines but failed to protect them or even inform them of the known dangers of uranium. Hundreds died early deaths, and many miners have filed claims against the U.S. government.

Today, proposed new uranium mining – using a supposedly safe process known as in situ leach mining – threatens to contaminate the only source of drinking water for 15,000 people on the Navajo Reservation in and around Crownpoint.

While the Capitans' activism has angered some fellow Navajos, including close relatives and friends who stand to make money from the proposed mine, they have persevered.

“I’m sorry. I don’t think you could do this and at the end say the water is going to be safe. Safe enough for our children and generations to come,” says Rita from her ENDAUM office. “We might double our pile of papers here, but that’s okay. We’re going to continue to fight.”

UPDATE: Rita & Mitchell launched an aggressive campaign to encourage the Navajo tribal council to vote on the issue. As part of the efforts, Homeland was shown at the Navajo Nation Museum, and at the Diné Biziil Coalition’s conference scheduled the day before the council went into session to vote. On April 19, 2005 The Navajo Nation Tribal Council passed a bill that bans conventional underground and open pit uranium mining and places a 25-year moratorium on uranium processing, including uranium ISL mining. The legislation, which is backed by ENDAUM and the affected chapters of Church Rock and Crownpoint, was sponsored by Delegate George Arthur and had the support of five standing committees of the Council.

Although a great victory, this is not the end of the fight by any means. The federal government can overrule this action. It is, however, an important first step for the Navajo people to present a united opposition to the uranium industry’s interests.

Barry Dana, Penobscot, Maine

Former Chief Barry Dana grew up on Indian Island on the Penobscot Reservation along the Penobscot River, where he was deeply influenced by his grandmother, one of the last speakers of the Penobscot Language. He says that their stories of living off the land in the "old ways" helped shape his love for both the natural world and Penobscot culture.

Indian Island, however, is just 30 miles downstream from the Lincoln Pulp and Paper Mill. Even as a child, when Dana swam in the river, he would emerge covered with blisters and rashes.

“Spending about half the summer in the water, I’d get these lesions on my legs,” says Dana. “So eventually I stopped swimming.”

In 1983, Dana graduated from the University of Maine at Orono with a bachelor's degree in education and an associate's degree in forest management. Since then, he has worked to educate people about the traditions of Maine’s indigenous nations and to help his people regain control of their culture and ancestral lands.

Dana, like many others in Maine, had come to believe that the Clean Water Act of 1972 had cleaned up the river that the Penobscot had depended on for centuries. In recent years, however, the people of Maine learned that Lincoln Pulp and Paper and other mills are still dumping deadly toxins in the river, with the state of Maine issuing penalties so small that the costs of dumping barely dent their multi-million-dollar budgets.

“Those fines amount to, on a yearly average, $3000,” says Dana. “$3,000 a year for basically the right to dump billions of gallons of untreated wastewater directly into our river.”

Today, with his people now unable to eat the fish, harvest the medicinal plants or swim in the river they hold sacred, Dana is battling the powerful paper companies and their allies in state government. Recently, he tried to get the federal EPA to maintain control over river quality. But instead the EPA voted to allow the state, notoriously controlled by paper-industry special interests, to monitor water quality along the river.

But even in defeat, Dana has vowed to continue his fight. “All over the country, thirty years of environmental protections are quietly being dismantled,” says Dana. “Sometimes it seems like many Americans are blind to what’s going on. But we don’t have the luxury of looking the other way. We can’t give up on the river.”